2019 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 64. Вып. 4 ИСТОРИЯ

ВСЕОБЩАЯ ИСТОРИЯ

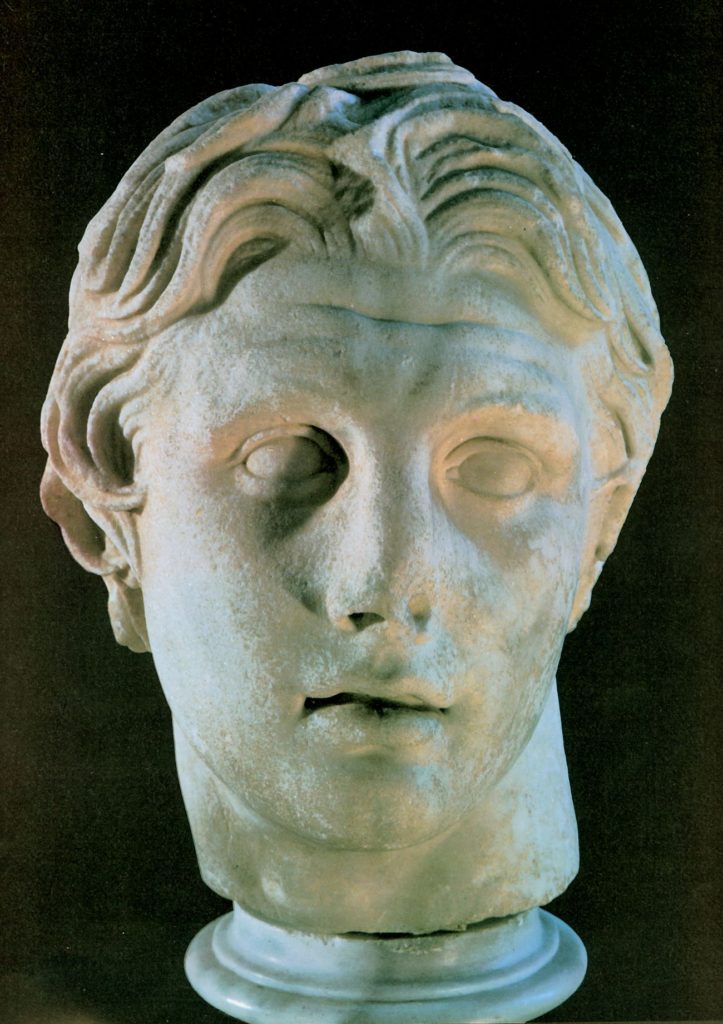

Alexander the Great and Three Examples of Upholding

Mythological Tradition

H. Tumans

For citation: Tumans H. Alexander the Great and Three Examples of Upholding Mythological Tradition. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 2019, vol. 64, iss. 4, рр. 1301–1316. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu02.2019.409

This article discusses three episodes from the history of Alexander the Great that illustrate his attitude towards ancient myths and religiosity. It is known that the great conqueror used myths for his own political goals, however, there are at least three episodes in which cultural context comes to the fore and plays a particular role in the king’s ideology. First, the profanation of Betis’ body after the seizure of Gaza. Despite many authors’ rebukes of his action, it can be seen that Alexander was imitating Achilles thus trying to strengthen his authority among the troops. The second example is demolition of a Branchidae village in Bactria. Surely, it is an inexcusable act according to secular understanding, but it is righteous from the point of view of traditional religiosity of ancient Greeks and Macedonians. There is strong reason to believe that Alexander thus rather increased than lost his authority since he acted as a defender of the traditional religion. The third episode is a story of Alexander’s meeting with the queen of the Amazons. It is impossible to determine whether the story is based on some historical fact, although it is often mentioned in sources. It is possible to suggest that Alexander had it staged in order to revive an ancient myth and emulate his legendary ancestor Heracles. These three episodes had no clear political meaning but carried a deeply symbolic character and placed the king into the world of ancient myths and figures. These, together with similar mythological symbols, indorsed the heroic ideology that served as the foundation for the great campaign. Keywords: Alexanderthe Great, mythos, religion, legitimization, tradition, Batis, Branchidae, Thallestris, heroic ethos.

Harijs Tumans — PhD, Professor, Latvijas Universitate, Latvijskaya Respublika, LV-1050, Riga,

Aspazijas bulvāris, 5; harijs.tumans@lu.lv

Харийс Туманс — PhD, профессор, Латвийский университет, Аспазиас бульвар, 5, Rīga, LV-

1050, Латвийская Республика; harijs.tumans@lu.lv

© Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет, 2019

Александр Великий и три примера использования мифологической традиции Х. Туманс

Для цитирования: Tumans H. Alexander the Great and Three Examples of Upholding Mythological Tradition // Вестник Санкт-Петербургского университета. История. 2019. Т. 64. Вып. 4. С. 1301– 1316. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu02.2019.409

В статье рассматриваются три сюжета из истории Александра Македонского, в которых проявляется его отношение к древним мифам и религиозным представлениям. Как известно, великий завоеватель использовал мифы в своих политических целях, однако есть как минимум три эпизода, в которых политический аспект выражен не столь ярко, зато отчетливо ощущается культурный контекст, имевший особое значение для идеологии царя. Во-первых, это поругание тела Бетиса после взятия Газы, чем многие античные авторы попрекали Александра. Однако если отбросить тенденциозность — как древнюю, так и современную, — можно увидеть, что этим поступком полководец и в самом деле подражал Ахиллесу и этим пытался укрепить свой авторитет в войске. Второй пример — это разрушение поселка Бранхидов в Бактрии. Поступок недопустимый с точки зрения светского сознания, но вполне благочестивый с точки зрения традиционной религиозности древних греков и македонцев. Есть все основания полагать, что, вопреки мнению как поздних античных, так и многих современных авторов, Александр таким образом не терял, а повышал свой авторитет в греческом мире, так как выступал в роли защитника традиционной религии. И наконец, третий эпизод — это рассказ о встрече с царицей амазонок. Невозможно определить, стоит ли за этим какой-нибудь невымышленный факт, но сама история нашла широкое отражение в источниках. Предположительно Александр совершил некую инсценировку, целью которой было оживить древний миф и уподобить царя его легендарному предку Гераклу. Все три случая не имели очевидного политического значения, но носили глубоко символический характер и вписывали царя в мир древних мифов и образов. Эти и подобные им мифологические символы поддерживали героическую идеологию, на которой строилась легитимация великого завоевания.

Ключевые слова: Александр Великий, миф, религия, легитимация, традиция, Бетис, Бранхиды, Телестрис, героический этос.

The history of Alexander the Great comprises several plots that revolve around his links with ancient myths and mythological ancestors. Generally, they have a symbolic and political character: throwing a spear into Asian soil, cutting the Gordian knot and visiting the oracle of Ammon, etc. However, there are a few episodes among them that stand out of the general context due to their non-political character and owing to the fact that they enable both ancient and contemporary authors to criticize Alexander. These three stories not only illustrate how Alexander used ancient mythological figures and religiosity for his own goals, but also aid in understanding the legitimation of the great eastern campaign.

The first of these episodes concerns punishing Betis after capturing Gaza. Gaza is known to have been taken by assault in 332 after a fierce resistance; moreover, Alexander was wounded twice there. Usually, all historians focus on this point. Curtius, however, adds the story about the punishment and torture of Betis — the commander of Gaza’s garrison. According to him, Alexander threatened to torture him, while Betis stared at him fearlessly and defiantly and did not utter a single word, which enraged the winner. The royal anger resulted in the following punishment: “Alexander’s anger turned to fury, his recent successes already suggesting to his mind foreign modes of behaviour. Thongs were passed through Betis ankles’ while he still breathed, and he was tied to a chariot. And Alexander’s horses dragged him around the city while the king gloated at having followed the example of his ancestor Achilles in punishing his enemy” [Curt. IV. 6. 29; translated by John Yardley].

It is assumed that the source of this story was an extract from Hegesias of Magnesia recounted by Dionisius of Halicarnassus [FGrH 142 F5][1]. Besides, this text has a distinctly grotesque and parodic character: “Now Leonatus and Philotas brought in Batis alive. Seeing that he was flashy and tall and very fierce-looking (he was in fact black) he was filled with hatred of his presumption and his looks and ordered them to put a bronze ring through his feet and drag him around naked” [Dion. Halic. De Compos. Verb. 18. 124; translated by Judith Maitland].

Interestingly, Dionisius uses this extract as an illustration of a bad writing style. It is clear to him that this is the imitation of Homer; therefore, to make a comparison he also quotes an extract from the “Iliad” describing how Achilles defiled the body of his defeated opponent Hector by dragging it behind his chariot. The contrast is very stark indeed. Thus, Dionisius draws the conclusion that the sophist from Magnesia wrote this text either because of his foolishness or as a joke [Ibid. 18.28]. Indeed, the text by Hegesias is a malicious parody of both Homer and Alexander. Contrary to him, Curtius relates the story of Betis’ punishment in a serious tone, making his account more dramatic by using literary means of expression. It is another reason for him to condemn the unbridled temper of the Macedonian conqueror.

Thus, despite the difference in styles, both authors draw obvious parallels between the act of Alexander and that of his mythical ancestor Achilles. And both turn this story against Alexander[2]. Besides, it is puzzling that other sources do not mention this event at all. It does not mean, however, that the episode in Gaza was just a literary fiction or part of a literary topos drawing parallels between Alexander and Achilles as some authors tend to think[3]. We do not have enough arguments to make this claim[4]; after all, there is nothing impossible in the outrageous treatment of Betis. Moreover, the literary tradition enables to assume that it was based on a real fact rather than on the mere imagination of the authors. The original source is not known to us, and we can only speculate about it. Even if we knew it, it would not give us enough grounds to make judgments about the history of the episode concerning Betis.

It seems to me that it is much more important to explain the silence of our main sources. Most probably, it is due to the outrageous character of the act committed by Alexander. It is not a coincidence that only the authors with a critical attitude to the king speak about it. Considering Justin’s particular criticism towards Alexander, it would be natural to see him among them, but he did not even mention the siege of Gaza. As to other authors, it can be assumed that they either did not want to discredit Alexander’s name or genuinely could not believe that he could have committed such an egregious act. Besides, we must remember that the histories of Alexander that have been preserved until nowadays were created by writers living in a later period who regarded Alexander’s act in Gaza as a barbaric deed, just as contemporary authors do[5]. Interestingly, Curtius condemns Alexander’s behaviour as the act committed under the influence of foreign culture. He strives to deprecate Alexander for adopting the Eastern erratic temper but does not pay any attention to the obvious parallel with the Homeric character even though the imitation of Achilles is the key point in this episode[6].

At the same time, it should be considered that Alexander’s deeds discussed by the latest writers of the enlightened era could look very differently in the eyes of the king himself and his associates, whose system of values was based on the heroic ideal of the epic type. For them, resembling Achilles in anger was as natural as resembling him in feats and fame. There could be nothing reprehensible in that although in this case it is a negative act, reproached even by Homer [Il. XXII. 395]. However, Homer forgives his hero everything and, naturally, the Macedonian army forgives its king who had every reason for such an “epic rage” (the stubborn resistance of Gaza, a wound in the shoulder [Curt. IV. 6.7–23; Arr. Anab. II. 27. 1–2]. However, it seems that Alexander deliberately acted so to show the strength of his epic spirit, not to yield to the power of his great ancestor. By acting like Achilles in anger, he did not embarrass himself, as intelligent writers in subsequent times used to think; on the contrary, it only enhanced his authority among the troops. Thus, we should talk about a thoughtful way of promotion rather than literary fiction. By the way, fate itself drew a very convincing parallel between the two heroes by taking the life of Alexander’s friend Hephaestion before his own death, just as Patroclus was taken from Achilles shortly before his death. Alexander only had to surpass his ancestor in the grandiosity of his friend’s burial, which he did [Diod. XVII. 110. 8; 115. 1–5; Plut. Alex. 72; Arr.VII. 14.1–10; XV. 1–3; Just. XII. 12. 11–12]. And it is a real story, not just a literary fiction…

In other words, the evaluation of Alexander’s act in Gaza fully depends on the system of values of the individual who speaks about it. And there can be paradoxes in this respect. For instance, Homer himself reproached Achilles for the outrageous treatment of Hector’s dead body. At the same time, in the late 19th century, in 1890, in enlightened Europe, where the prevailing customs were much milder than those of Homeric times, Elisabeth of Bavaria, known as Sisi, commissioned a monumental painting for her palace on the island of Corfu that depicted Achilles riding around Troy on his chariot and dragging the body of defeated Hector behind him. Apparently, a delicate and beautiful empress did not see anything wrong in Achilles’ act. Therefore, it is safe to assume that rough Macedonian soldiers had many more reasons to admire their king when he repeated the act of Achilles regarding Betis.

Therefore, I believe that this fact really happened, and we can understand and adequately explain it only through the prism of the ideology of heroism, which underpinned Alexander’s actions. The essence of this ideology does not lie in the imitation of individual heroes of antiquity — Achilles, Heracles, Dionysus, but in pursuing the heroic ideal in general. That is why Alexander strove to be the first in battle[7]; he personally led troops into attack, engaged in hand-to-hand combat and was the first to scale the walls, which once nearly cost him his life [Diod. XVII. 60. 1–4; 98. 4–99; Curt. VIII. 4. 9–10; Plut. Alex. 16; 63; Arr. Anab. I. 2. 4; I. 15. 3; II. 23.4–5; III. 4. 13; VI. 9. 3–6. etc.]. Moreover, according to Nearchus, friends scolded Alexander for his passion for personal involvement in battles [Arr. Anab. VI. 13. 4]. This can be supplemented with the details of our sources that Alexander was looking for a duel with Darius. Since the duel did not take place[8], there is no need to see literary fiction in this, but, if we recognize that Alexander followed the norms of the heroic ethics, his desire for a duel is more than natural. Indeed, only with the idea of emulating the heroic ideal can his unquenchable thirst for fame and personal involvement in battles be explained. Exposing oneself to such a risk would be completely unwise for a commander in terms of common sense, but it is quite natural from the standpoint of Homer’s ethics, which, apparently, was the main motivating factor for the young conqueror of the world.

All of this suggests that Alexander was not playing “the hero” jokingly, only to inspire his troops, as many believe nowadays[9]. In fact, he did it seriously[10] as he often risked his life, which shows that he felt like a hero, heir and competitor to the ancient heroes. Thus, it is natural that he performed symbolic deeds, showing his attempt to imitate the great heroes by acquiring the shield of Achilles in Troy [Diod. XVII. 18; Arr. Anab. I. 11. 7–8][11], hunting for lions [Curt. VIII. 1. 14–17; 6. 7; Plut. Alex. 40][12], organizing all kinds of competitions throughout the whole campaign [Plut. Alex. 72; Arr. Anab. III. 1. 4; VII. 14. 1; VII. 14. 10. etc.], and erecting new “Pillars of Heracles” at the final point of the campaign [Diod. XVII. 95. 1–2; Curt. IX. 3. 19; Plut. Alex. 72; Arr. Anab. V. 29. 1–2]. Moreover, by emulating the heroes of the past, he became famous for his truly epic generosity (Diod. XVII. 40 1; 65. 3–4; 74. 3–5; Plut. Alex. 24; 40; Arr. Anab. III. 19. 5; V. 26. 89; VII. 4. 8; VII. 5. 1–6; VII. 12. 1–2. etc.]. Thus, the episode with Betis fits in the general trend perfectly and can be regarded as one of Alexander’s symbolic acts, the purpose of which was to demonstrate commitment to the heroic ideal.

However, the imitation of ancient heroes could have had some sense for Alexander only if his aspiration for the heroic ideal was shared by his soldiers. There are several stories in the sources that confirm this assumption. The first one concerns the siege of Halicarnassus: according to Arrian, one evening two Macedonian hoplites living in one tent got drunk and began arguing about their own prowess and deeds; to prove their point, they took their arms and started climbing the enemy wall, which resulted in a spontaneous clash between two armies [Аrr. Anab. I. 21. 1–4]. This story gives an insight in the mood of his soldiers, i.e., in their infatuation with heroic spirit. Another similar episode refers to the Indian campaign and is related by Curtius. When both armies stood there separated by the Hydaspes River, several young Macedonians led by two high-born youths rashly decided to attack the Indians on one of the islands at the time when they were off-duty; as a result, all of them perished in this adventure [Curt. VIII. 13. 13–15]. Curtius condemns their rashness and lack of prudence; he does not understand that the Macedonians perceived it as the expression of military valour and heroism, which fully conformed to the epic spirit. The third episode is a story recounted by Diodorus and Curtius about the contest between two military commanders — the Macedonian general Erygius and the Persian general Satibarzanes [Diod. XVII. 83. 5–6; Curt. VII. 4. 33–40]. It should be noted that after Erygius’ victory the Persians refused to continue fighting and gave themselves up to Alexander[13]. Apparently, it was the manifestation of a very ancient archetype of a heroic encounter of two leaders that had to determine the outcome of the conflict. Not only the Greeks, but also other ancient nations were familiar with this archetype [Il. III. 245–382; XXII. 131–371; Strab. VIII. 3. 33; 9. 1. 7], the evidence of which is the well-known biblical stories of David and Judith [1 Reg. 17. 51; Judith. 15. 1–2][14]. Therefore, such stories of a ritualized duel could not have been just a literary fiction as it does not make sense; moreover, both Diodorus and Curtius regarded the practice of ritual encounters as something archaic and forgotten.

It is noteworthy that Arrian tells another story about an encounter where Ptolemy defeated the leader of the Indians and took his armour according to an epic custom [Arr. IV. 24. 3–5]. There is no reason to regard it as a literary “calque”[15], bearing in mind that Homeric heroes really served as role-models for the Macedonian soldiers. Besides, the desire to possess the armour of the defeated enemy commander is so natural for a warrior that no literary prototypes are needed for that.

Finally, there could be added a story about a mock battle arranged by some camp-followers on the eve of the Battle of Gaugamela who divided themselves into two bands — the “Persians” and the “Macedonians” [Plut. 31]. Interestingly, Alexander perceived it as an omen of the future and ordered the leaders of both groups, one of whom represented Darius, but the other — the Macedonian King, to fight in a single combat [Ibid.]. Regardless of our attitude to this story, it obviously illustrates the spirit of military valour which pervaded the entire army — from the commanders to the camp-followers.

All these stories can certainly be perceived as fiction, but, if it is not possible to prove it, there is no reason to do it. On the contrary; there is much more reason to regard them as authentic as they represent only separate, unconnected episodes scattered among different texts without any relation to Alexander or his propaganda. Consequently, there is no need to falsify them. On the other hand, the very fact of the existence of these stories implies the existence of high fighting spirit in the Macedonian army. Naturally, the king also had the same spirit, was inspired by it and inspired his soldiers. Besides, it should be pointed out here that this fighting spirit was not just military boldness, but the deliberately cultivated heroic ideal of Homeric type.

In this context, it becomes clear that the desecration of the body of Betis had a symbolic character both for Alexander and his soldiers and was perceived through the prism of the epic system of values.

The next episode is Alexander’s destruction of the village of the Branchidae as a punishment for the treason of their forbears who had sided with the Persians and desecrated the Milesian temple of Apollo. This event is mentioned in several sources, and there is one detailed description — by Curtius. We find the first mention of this episode in Diodorus’ text: “How the Branchidae, having been settled long ago by the Persians at the extremity of their kingdom, were destroyed by Alexander as traitors of the Greeks” [Diod. XVII. Content; translated by C. H. Oldfather]. Then, Strabo, probably based on Callisthenes’[16] account, gives a concise report without any emotions and evaluations: “And near these places, they say, Alexander destroyed also the city of the Branchidae, whom Xerxes had settled there — people who voluntarily accompanied him from their home-land — because of the fact that they had betrayed to him the riches and treasures of the god at Didyma. Alexander destroyed the city, they add, because he abominated the sacrilege and the betrayal” (Strab. XI. 11.4 С518; translated by H. L. Jones.). Plutarch expresses his evaluation in one brief comment: “Not even the admirers of Alexander, among whom I count myself, approve his wiping out the city and destroying the entire manhood because of the betrayal of the shrine near Miletus by their forefathers” (Plut. Mor. 557B; translation by N. G. L. Hammond).

Curtius, however, surpassed all of them — he did not spare colours in his usual style condemning Alexander for unmotivated cruelty: “The unarmed wretches were butchered everywhere, and cruelty could not be checked either by community of language or by the draped olive branches and prayers of the suppliants. At last, in order that the walls might be thrown down, their foundations were undermined, so that no vestige of the city might survive. As for their woods also and their sacred groves, they not only cut them down, but even pulled out the stumps, to the end that, since even the roots were burned out, nothing but a desert waste and sterile ground might be left. If this had been designed against the actual authors of the treason, it would seem to have been a just vengeance and not cruelty; as it was, their descendants expiated the guilt of their forefathers, although they themselves had never seen Miletus, and so could not have betrayed it to Xerxes” (Curt. VII. 5. 33–35; translated by John Yardley). Finally, this story is mentioned in Sud Lexicon: “the foresight of the god did not slumber’, but Alexander killed them all and they disappeared” (Sud. s.v. Βραγχίδαι; Ael. Fr. 54; translated by Suda on Line project).

According to the modern-day fashion of exposing Alexander, contemporary scholars not only eagerly accept the historicity of this fact[17][18], with some exceptions[19], but also qualify his act as a crime, following Curtius[20]. The willingness of the contemporary mind to condone the behaviour of the Branchidae and accuse Alexander of genocide, as Olga Kubica[21] does it, is natural. The point of view of the ancient people is not taken into account as it is a priori regarded as false. Usually, scholars search for Alexander’s political motives and highlight his interest in controlling the oracle at Didyma[22]. A good illustration of that is the position of Parke: on the one hand, he admits that the position of Callisthenes — our primary source in this case22 — presented the official version of this event, according to which Alexander committed a just act of revenge on the Branchidae[23]. On the other hand, Parke does not accept this version, looking for the political motives of violence, and assumes that it was caused by Alexander’s desire not to give the Branchidae access to the temple of Apollo restored by the Milesians. As a result, it enables him to speak about the moral decline of Alexander[24]. Kubica develops this idea further suggesting that the concept of revenge was invented ex eventu to conceal the political motives of violence[25]. This approach seems to be anachronistic and artificial; it does not consider the mentality of the people living at that time. First, the idea of revenge was natural and self-evident for the people of the given period; second, one political decision in Miletus or in Alexander’s headquarters would have been enough to ban the Branchidae from entering the new sanctuary, and there would have been no need to kill anyone.

I find the position of Hammond, who explains the revenge taken on the Branchidae by a specific character of Alexander’s thinking, to be more valid. Alexander had close ties with the cult of Apollo, and he wanted to punish the Branchidae, just like his father had punished the Phocians for ransacking the Delphic oracle, and he had punished the Thebans for treachery[26]. Moreover, I would like to add another aspect: by taking revenge on the Branchidae, Alexander demonstrated his commitment to traditional Hellenic religiousness which underpinned the legitimation of his military expedition. From the perspective of this religiousness, there is no reason to reproach Alexander; after all, the gods punish sinners to the seventh generation; consequently, he only committed the act of divine vengeance. Apparently, a number of contemporary scholars are misled by Curtius, who does not believe in metaphysics and does not want to notice religious motives in Alexander’s actions[27]. We must bear in mind that both in Alexander’s lifetime and later the thinking of many people was determined by religious notions. Therefore, it is stated in the Suda Lexicon that Alexander exterminated the Branchidae as he regarded them as criminals just like their forbears: “so he killed them all, judging that the offspring of evil is evil” [Sud., s.v. Βραγχίδαι; Ael. Fr. 54; translated by Suda on Line project]. It was right from the perspective of classical Greek religion. It was equally right from the perspective of the philosophical religion of Plutarch, who justified the divine punishment in the following generations (Plut. De sera numinis vindicta)[28].

There can be found a lot of evidence of Alexander’s traditional religiousness in the sources[29]. Firstly, every morning he sacrificed to gods with his own hands [Plut. Alex. 76; Arr. Anab. VII. 25. 1–5]; secondly, there is plenty of evidence in sources describing him sacrificing for various reasons[30]. However, modern critical authors explain all these (and similar) facts only by official propaganda[31]. Thus, they present him as a Machiavellian ruler, cynical and non-religious, motivated purely by pragmatic considerations[32]. But what are the reasons behind this? Clearly, there is only one — the modern trend of critical attitude towards Alexander prevalent in the literature of recent decades. The context of the ancient sources indicates the exact opposite — the true and lively religiosity of Alexander.

Some more reasons can be given in favour of this idea. Firstly, half of the religious actions described in the sources would have been enough for political promotion. It is easy to see reading the text with an open mind that most of the described offerings were not done simply to “obey the norms” but due to the internal need of Alexander, his reaction to certain events (e. g., the gratitude for a victory, some kind of achievement or the elimination of a threat), i. e. all completely in keeping with the spirit of Homeric heroes. Apparently, that is why the sources pay special attention to this; otherwise it is difficult to understand the distraction by something that goes without saying. It can also be mentioned that the history of Alexander is unique in this sense as the factor of religiosity of other commanders was much less mentioned in the biographies of antiquity. Moreover, if the festivities and offerings can still be called a formality and political promotion, Alexander’s fascination with oracles, prophets, signs and dreams cannot be explained by formalism and simple imitation any more — as has already been pointed out, it constituted his true mental system[33]. It is well known that Alexander was always accompanied by diviners and interpreters of signs — first, it was his trustworthy Aristander [Arr. Anab. I. 25. 1–8; II. 26. 4; III. 2. 1–2; Plut. Alex. II, XIV; Curt. VII. 7. 8–29 etc.] as well as a whole group of prophets, among whom a certain Demophones and a Syrian woman “overtaken by a divinity” are distinguished by sources [Diod. XVII. 98. 3–4; Curt. V. 4. 1; VII. 7. 8; Plut. Alex. 24, 26; Arr. Anab. IV. 13.5. etc.]. In addition, Alexander himself would both receive and successfully interpret the signs when demanded so by circumstances (for instance, interpreting the words of Pythia before the campaign [Plut. Alex. 14]; successfully explaining the sign of an eagle on the ground next to a ship during the siege of Miletus (Arr., I, 18, 7–9]; expounding the dream by Tyre [Curt. IV. 2. 17; Arr. Anab. II. 18. 1; Plut. Alex. 24] and while establishing the city of Alexandria [Plut. Alex. 26][34]. One can only wonder how a disciple of Aristotle could have had such a passion for mysticism. Nonetheless, it should be recognized as a fact. And finally, it should be admitted that it is no coincidence that the same Arrian calls Alexander the “most diligent admirer of gods” — in the superlative form [Arr. Anab. VII. 28.1].

Alexander’s archaic religiosity is associated with another story in his history mentioned by all our main sources. This story refers to his relationship with Thallestris, the queen of the Amazons, who came to see Alexander to conceive his child. It can be easily noticed that Diodorus, Curtius and Justin give their own versions of the same story where most of the details are similar [Diod. XVII. 77. 1–3; Curt. VI. 5. 24–32; Just. XII. 3. 5–7]. Therefore, it is very probable that Cleitarchus was the original source[35]. Anyway, Diodorus gives the oldest and the most concise version of the story: “When Alexander returned to Hyrcania, there came to him the queen of the Amazons named Thallestris, who ruled all the country between the rivers Phasis and Thermodon. She was remarkable for beauty and for bodily strength and was admired by her countrywomen for bravery. She had left the bulk of her army on the frontier of Hyrcania and had arrived with an escort of three hundred Amazons in full armour. The king marvelled at the unexpected arrival and the dignity of the women. When he asked Thallestris why she had come, she replied that it was for the purpose of getting a child. He had shown himself the greatest of all men in his achievements, and she was superior to all women in strength and courage, so that presumably the offspring of such outstanding parents would surpass all other mortals in excellence. At this the king was delighted and granted her request and consorted with her for thirteen days, afterwards he honoured her with fine gifts and sent her home” [Diod. XVII. 77.1–3; translated by C. H. Oldfather].

It should be noted that Diodorus did not show his attitude to this story in any way, neither did Justin and Curtius, who are usually critical of Alexander; in this case, however, they did not even try to oppose him or sneer at him. Apparently, this is because they found a way to turn this story against Alexander. It was probably initiated by Diodorus, who started talking about Alexander’s moral decline right after the story of the Amazons by reproaching him of enjoying Persian luxury and effeminacy [Diod. XVII. 78.1–3]. Curtius and Justin followed the same pattern, emphasizing that after the visit of the queen of the Amazons the king degenerated and became arrogant [Curt. VI. 6. 1–9; Just. XII. 3. 9–11]. Justin, for instance, describes it in the following way: “Soon after (Post haec), Alexander assumed the attire of the Persian monarchs, as well as the diadem, which was unknown to the kings of Macedonia, as if he gave himself up to the customs of those whom he had conquered” [Just. XII. 3.8; translated by J. S. Watson].

Other authors, who are not so biased, are very sceptical about the story of the Amazons. Strabo regards it as another fragment of fiction invented by court flatterers and adds that reliable authors do not even mention it [Strab. XI. 5. 3–5 C505]. Plutarch presents different opinions concerning this story and expresses his scepticism by hinting that it could have been caused by the fact that Alexander wrote in one of his letters that the Scythian king had sent him his daughter as a wife [Plut. Alex. 46]. Arrian also points out that serious authors do not mention the Amazons, and he regards Alexander’s meeting with them as impossible because they had already vanished from Asia by that time; besides, he tries to find a rational explanation for these stories and suggests that Atropates, the satrap of Media, sent a hundred of women to Alexander dressed as the Amazons [Arr. Anab.VII. 13. 2–5].

Surely, contemporary scholars are even more sceptical about the Amazons than ancient authors. Similarly to Arrian, they wonder what could have been the cause for creating this legend. Some scholars consider Arrian’s version about Atropates’ gift as the most probable explanation[36]. Others follow Plutarch and believe that the story could have stemmed from the offer of the Scythian king extended to Alexander to take his daughter as a wife, or it could have been Alexander’s marriage with Roxana, which was part of his policy of bringing different peoples together[37]. This version is certainly quite witty, and it would be tempting to regard Roxana as the prototype of Thallestris, but it should be admitted that all these versions are fictitious, forced and artificial.

In my view, the root of the legend should not be sought in some external events, as Plutarch and Arrian did it, but in the semantics of images. Two aspects need to be mentioned in this respect. First, if we consider the specific features of the mythological perception of the world, it is easy to notice the ancient concept of sacred marriage — hieros gamos in the relationship of Alexander and Thallestris. From this perspective, this story can be regarded as the marriage of the strongest man — a warrior and winner — and the strongest female warrior. According to the mythological matrix, this plot should result in the birth of an outstanding person, the progenitor of an outstanding tribe. Admittedly, the history keeps silence about the consequences of this marriage, and only Justin mentions that the Amazonian queen left when she was convinced that she was pregnant [Just. XII. 3. 7]. On the other hand, we know a Greek myth embodying this mythologem. It is a story by Herodotus about Heracles’ romantic entanglement with a local goddess in Crimea, partly a serpent and partly a woman, who gave birth to three of his sons, one of whom named Scythes became the progenitor of the Scythians [Hdt. IV. 8–10].

In this context, it seems obvious to me that the story about Alexander’s marriage with Thallestris replicates the same plot and equates the king to Heracles — a mythical forefather of the dynasty of Macedonian kings, whom Alexander tried to surpass during his expedition. There is abundant literature about the role of the image of Heracles in Alexander’s ideology, and there is no need to repeat it here[38]. We have a good reason to believe that the legend about the Amazonian queen was created to support Alexander’s ideologems about his rivalry with the famous ancestor. It is also possible that some performance was created for this purpose in order to put the myth into life.

Thus, all three stories discussed here — about Betis, the Branchidae and Thallestris — placed Alexander in the world of ancient myths and archaic religious ideas. These accounts did not play an obvious political role but had a vivid symbolic character. These were mythological symbols that created the ideological basis for the legitimation of great conquests.

To better understand the significance of the mental factor in the system of the legitimation of Alexander’s campaign, we should not forget that ancient Greeks and Macedonians had other concepts of legitimation different from ours. They did not have our understanding of the constitution; they were not familiar with our legal thinking, and even the Roman law did not exist yet. Therefore, the legitimation of their statuses and actions was based not only on law, but also on religion, traditions and moral norms, which were even more important since they were inherited from ancestors[39]. A vivid evidence of this is the ancient Greek idea about two types of laws — written and unwritten ones. The unwritten laws referred to the so-called “ancestral customs” (patria ethe) which were accepted in the society but were not written down in statutes. This can also be formulated as the existence of formal and informal rules of life as legitimate bases for political actions in the Greek society. Moreover, the informal unwritten norms were so important that even Plato and Aristotle gave them due credit [Plat. Politicus. 298d-e, 301a; Leges. 793b-d; Arist. Pol.

1287b] and regarded them as an integral part of any well-organized state. In fact, Aristotle deemed them more important than written laws[40]. This could be the reason why Plutarch believed that Lycurgus forbade to put laws in writing so that they would conform to the sacred unwritten tradition [Plut. Lyc. 13]. Plutarch might have been right in this respect.

There is a vivid example in Greek culture illustrating the opposition of written and unwritten laws — it is “Antigone” by Sophocles. That is how Aristotle, whose authority we certainly trust, interprets the main conflict in this tragedy [Arist. Rhet. 1373b4-5, 8–12]. In fact, it is clearly stated in the words uttered by Antigone herself, in which the unwritten law is put above the written law issued by the authorities [Soph. Antig. 445–453]. The moral truth as well as the sympathies of the author and his audience belong to Antigone, i.e. to the unwritten informal law[41]. In real life, the fate of Antigone was replicated by Socrates[42], who also accepted death for the sake of higher moral truth. It should be noted that the classical Athenian judicial practice was based not only on the formal aspects of the case and the letter of the law, but also on informal truth, which does not fit into the Procrustean bed of the written law. As Lysias aptly noted, judicial practice served for the “good of the people”, i.e., for their edification [Lys. 6. 54]. It was edification rather than the triumph of the letter of the law. The court did not focus on the judicial side of the case but tried to clarify the “nature” of the defendant, i.e., his way of thinking and characteristics both as a person and a citizen; after all, it was a person that was tried rather than a crime [see, for example: Andoc. I. 146sqq; Dem. XIX. 16; XXV. 30; Lys. V. 3; X. 23; XXIV. 1; XIV. 17, 23; XXX. 1; Arist. Rhet. 1365a5 sqq, 1374b10. etc., etc.][43]. This implies the priority of unwritten informal truth compared to the written formal law. In this context, the existence of informal legitimation underpinned by morality and the general ideas of justice and righteousness rather than the law is perfectly natural.

Consequently, if Alexander wanted to secure the understanding and support for his cause in the Greek world, he had to build the legitimation of his campaign on two foundations — the formal[44] and the informal ones. Indeed, from the formal point of view, his campaign was presented as the war of revenge against the Persians and the liberation of the Greeks in Asia Minor[45]; informally, it was a heroic war, an act of heroism both on his part and on the part of his soldiers[46]. There is good reason to assume that the heroic aspect was more important to Alexander, and that is why he imitated ancient heroes and competed with them. Therefore, a spear thrown into the soil of Asia at the very beginning of his expedition can be regarded as the main symbol of his war [Diod., XVII. 17. 2; Arr. Anab. I. 11. 5–7; Just. XI. 5; XI. 6, 10–11]. In fact, the whole ideology of heroic contest is built around this image, which created the field of informal legitimation. The Hellenic concept of land ownership by right of “conquest with a spear” (hora doriktetos)[47] also stems from it. In fact, the idea of the “right of a spear” is very old[48], and it is first mentioned in the “Iliad”, where Achilles — Alexander’s prototype — refers to Briseis as the captive of his spear [Il.9. 343]. It should be reminded here that in the epic world, which served as a model for Alexander, warfare was regarded as the most respectable way of earning a living, and Homeric heroes not only engaged in robbery but also boasted about it [Il. XI. 670 — 682; Od. II. 70–74; III. 105–107; IX. 252–257; XI. 71–74; XIV. 229–234; XXI. 15–30]. Therefore, it is more than natural that, following ancient examples, Alexander presented his expedition as the realization of the age-old “right of a spear”. Both he and his soldiers were fed by the heroic ideals of glory and valour, which were provided by numerous examples from the world of myths.

All that explains why Alexander maintained and cultivated a peculiar mental environment around himself woven from myths and prophecies. After all, the heroic ethos that fed his ideology was underpinned by archaic religiousness and ancient myths. Therefore, Alexander revived ancient myths and created new myths around himself. The three examples discussed in this article show how Alexander maintained the ideological matrix of heroism during his campaign, skilfully manipulating with images and notions inherited from ancient myths.

References

Atkinson E. A. A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus’ Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 3, 4. Amsterdam, Adolf M. Hakert, 1980, 284 p.

Atkinson E. A. A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 5 to 7,2. Adolf M. Hakert, 1994, 284 p.

Austin M. Alexander and the Macedonian Invasion of Asia: Aspects of the Historiography of War and Empire in Antiquity. Alexander the Great. Ed. by I. Wortington. New York, Routlege, 1995, pp. 18–135.

Badian E. The Deification of Alexander the Great. Ancient Macedonian Studies in Honor of Charles F. Edson. Ed. by H. J. Dell. Thessaloniki, Institute for Balkan Studies, 1981, pp. 27–71.

Badian E. Alexander the Great between Two Thrones and Heaven: Variations on an Old Theme. Subject and Ruler: The Cult of the Ruling Power in Classical Antiquity. Papers Presented at a Conference Held in the University of Alberta on April 13–15, 1994, to Celebrate the 65th Anniversary of D. Fishwick. Ed. by A. Small. Ann Arbor, 1996, pp. 11–26.

Baynham E. Alexander and the Amazons. Classical Quarterly. New Series, 2001, vol. 51, 1. pp. 115–126.

Bengtson H. Philipp und Alexander der Grosse. Die Begründer der hellenistischen Welt. München, Callwey Publ.,1985, 320 s.

Berve H. Wesenzüge der Griechischen Tyrannis. Die ältere griechische Tyrannis bis zu den Perserkriegen. Hrsg. K. Kinzl. WDF Publ., Darmstadt, 1979, ss. 165–182.

Bettenworth A. Jetzt büßten die Nachfahrer die Schuld ihrer Ahnen. Das Problem der Branchidenepisode bei Curtius Rufus. Der römische Alexanderhistorker Curtius Rufus. Hrsg. H. Wulfram. Wien, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2016, ss. 189–208.

Billows R. King and Colonists (Aspects of Macedonian Imperialism). London, Brill, 1995. 253 p.

Bosworth A. B. Conquest and Empire. The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993, 330 p.

Briant P. Darius in the Shadow of Alexander. Transl. by J. M. Todd. Harward,Harward University Press, 2015, 606 p.

Brunt P. A. The Aims of Alexander. Alexander the Great. Ed. by I. Wortington. London, Routledge, 2003, pp. 5–53.

Carney E. Hunting and the Macedonian Elite: Sharing the Rivalry of the Chase. The Hellenistic World.

Ed. by D. Ogden. London, Classical Press of Wales and Duckworth, 2002, pp. 59–80.

Chaniotis A. War in the Hellenistic World: A Social and Cultural History. Oxford, Willey-Blackwell, 2005, 336 p.

Colaiaco J. A. Socrates against Athens: Philosophy on Trial. New York, Routledge, 2001, 278 p.

Demandt A. Alexander der Große. Leben und Legende. München, C. H. Beck, 2009, 655 p.

Dreyer B. Heroes, Cults, and Divinity. Alexander the Great. A New History. Eds W. Heckel, L. A. Tritle. Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 218–234.

Ehrenberg V. Sophocles and Pericles. Oxford, Blackwell, 1954, 256 p.

Flower M. Alexander the Great and Panhellenism. Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Ed. by A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 96–135.

Fontenrose J. Didyma: Apollo’s Oracle, Cult and Companions. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1988, 282 p.

Fredricksmeyer E. Alexander’s Religion and Divinity. Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great. Ed. by J. Roisman. Leiden, Brill, 2003, pp. 253–278.

Fredricksmeyer E. Alexander the Great and the Kingship of Asia. Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction.

Eds A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 136–166.

Garlan Y. War in Ancient World: A Social History. London, Chatto and Windus, 1975, 200 p.

Habicht C. Gottmenschentum und Griechische Städte. 2. Aufl. München, C. H. Bek‘sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1970. 290 s.

Hammond N. G. L. The Branchidae at Didyma and in Sogdiana. Classical Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 2, 1998, pp. 339–344.

Heckel W. Alexander, Achilles and Heracles: Between Myth and History. East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honour of Brian Bosworth. Eds P. Wheatlet, E. Baynham. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 21–33.

Hoffman W. Die Polis bei Homer. Festschrift für Bruno Snell. Hrsgb. H. Erbse. München, Beck, 1956, ss. 153– 165.

Huttner U. Die politische Rolle des Heraklesgestalt im griechischen Herrschertum. Stutgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1997, 388 s.

Instinsky H. U. Alexander der Grosse am Hellespont. Würzburg, Helmut Kupper Verlag, 1949, 72 s.

Kholod M. M. The Cults of Alexander the Great in the Greek Cities of Asia Minor. Klio. Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte. 2016, bd. 98.2, pp. 495–525.

Kubica O. The Massacre of the Branchidae: a Reassessment: The Post Mortem Case in Defence of the Branchidae. Alexander the Great and the East: History, Art, Tradition. Eds K. Nawotka, A. Woiciehowska. Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 2016, pp. 143–150.

Maitland J. Never Aid God. Alexander the Great and the Anger of Achilles. East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honour of Brian Bosworth. Eds P. Wheatley, E. Baynham. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 1–20.

Mehl A. Drive Country. Kritische Bemerkungen zum “Speererwerb” in Politik und Volkerrecht der hellenistischen Epoche. Ancient Society, 1980/81, vol. 11/12, pp. 173–212.

Nawotka K. Alexander the Great. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, 440 p.

Nilsson M. Geschichte der griechischen Religion. Bd. 2. München, Münchner Jahrbuch der Bildenden Kunst, 1955, 835 s.

Palagia O. Hephaestion’s Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander. Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Eds A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 167–206.

Parke H. W. The Massacre of the Branchidae. Journal of Hellenic Studies, 1985, vol. 105, pp. 59–68.

Perrin B. The Genesis and Growth of Alexander Myth. Transactions of the American Philological Association, 1895, vol. 26, pp. 56–68.

Roisman J. Honor in Alexander’s Campaign. Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great. Ed. by J. Roisman. Leiden, Brill Publ., 2003, pp. 279–321.

Sancisi-Weerdenburg H. The Tyranny of Peisistratos. Peisistratos and the Tyranny: A Reappraisal of the Evidence. Ed. by H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg. Amsterdam, J. C. Gieben, 2000, pp. 3–23.

Surikov I. E. Ancient Greece. Mentality, Religion, Culture. Moscow, Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury, 2015, 720 p. (In Russian)

Taeger F. Charisma. Studien zur Geschichte des antiken Herrschekultes. Bd. 1. Stuttgart,W. Kohlhammer Verlag, 1957, 717 s.

Tarn W. Alexander the Great. Vol. 2.Cambridge, Cambridge University Press,1948, 176 p.

Tarn W. Alexander der Grosse. Bd.1.Darmstadt, WBG, 1968.

Tarn W. The Massacre of the Branchidae. Classical Revue, 1922, vol. 36, pp. 63–66.

Tondriau J. Alexandre le Grand assimilé à differentes divinitè. Revue de Philologie, de Littèrature et d‘Histoire Anciennes, 1949, vol. 75(23), pp. 41–52.

Valloirs R. Alexandre et la mystique dionysiaque. Revue des Etudes Anciennes, 1932, vol. 34, pp. 81–82.

Waterfield R. Why Socrates Died:Dispelling the Myths. London, W. W. Norton & Company Publ., 2009, 288 p.

Welwei K.-W. Athen. Von neolitischen Siedlungsplatz zur archaischen Grosspolis. Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgfesellschaft, 1992, 305 s.

Wilcken U. Alexander der Grosse. Leipzig, Quelle & Meyer, 1931, 315 s.

Wortington I. By the Spear. Philip II, Alexander the Great and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2004, 416 p.

Received: April 4, 2019

Accepted:

September 9, 2019 Статья поступила в редакцию 4 апреля 2019 г. Рекомендована в

печать 9 сентября 2019 г.

[1] See: Maitland J. ΜΗΝΙΝ ΑΕΙΔΕ ΘΕΑ. Alexander the Great and the Anger of Achilles // East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honour of Brian Bosworth. Eds P. Wheatley, E. Baynham. Oxford, 2015. P. 5. — It does not mean, however, that Hegesias was the first and only source: Atkinson E. A. A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus’ Historiae Alexandri Magni. Books 3 und 4. Amsterdam, 1980. P. 344.

[2] Maitland J. ΜΗΝΙΝ ΑΕΙΔΕ ΘΕΑ… P. 7; Heckel W. Alexander, Achilles and Heracles: Between Myth and History // East and West in the World Empire of Alexander. Essays in Honour of Brian Bosworth. Eds P. Wheatlet, E. Baynham. Oxford. P. 29, 33 f.

[3] See: Perrin B. The Genesis and Growth of on Alexander Myth // TAPA, 26, 1895. P. 56–68; Tarn W. Alexander the Great. Vol. II. Cambrige, 1948. P. 267 f; Atkinson E. A. A Commentary… P. 341; Heckel W. Alexander, Achilles and Heracles… P. 18 f.

[4] I fully agree with Bosworth who believes that Arrian’s ignoring it cannot be the reason for denying this historical episode with Betis: Bosworth A. B. Conquest and Empire. The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambrige, 1993. P. 68.

[5] Nawotka K. Alexander the Great. Cambrige, 2010. P. 198.

[6] There can also be observed some differences: Achilles dragged Hector’s dead body behind his chariot, whereas Betis was still alive. However, it is not the reason to regard the parallel with Achilles and Hector as incorrect — see: Atkinson E. A. A Commentary… P. 341. — It is more than obvious that only Homer’s Achilles could serve as the prototype for this act. The fact that Betis was still alive was a “technical” detail that did not change the essence of the matter, but only put Alexander in a bad light. Therefore, the historicity of this detail can be doubted because this story was brought to us by the authors whose attitude to Alexander was not favourable.

[7] See: Roisman J. Honor in Alexander’s Campaign // Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great. Ed. by J. Roisman. Brill, 2003. P. 282–289.

[8] However, some legend about two kings meeting in battle was still created (Just.XI. 9. 9; Plut. Alex. XX). See more in: Briant P. Darius in the Shadow of Alexander. Transl. J. M. Todd. Harward, 2015. P. 147– 149.

[9] Tondriau J. Alexandre le Grand assimilé à differentes divinitès // Revue de Philologie, de Littèrature et d’Histoire Anciennes. 1949. T. 75(23). P. 41–52.

[10] Thankfully, there are other researchers who think similarly: Vallois R. Alexandre et la mystique dionysiaque // Revue des Etudes Anciennes, 1932. No. 34. P. 81–82.

[11] This fact illustrates the belief in the magical power of weapons, which is rooted in a very distant past — see: Taeger F. Charisma: Studien zur Geschichte des antiken Herrscherkultes. Bd. I. Stuttgart. S. 185.

[12] On the symbolic and political meaning of the lion hunt as a “sport” truly befitting a king, especially in the Macedonian context, see: Carney E. Hunting and the Macedonian Elite: Sharing the Rivalry of the Chase // The Hellenistic World. Ed. by D. Ogden. London, 2002. P. 60 f.; Palagia O. Hephaestion’s Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander // Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Eds A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, 2000. P. 167–206.

[13] There is some discrepancy in the sources: According to Diodorus and Curtius, Erygius was the winner, and he even brought the head of the defeated enemy to his king; according to Arrian, both opponents perished, but the barbarians took to flight [Arr.3. 28. 3]. It does not change the essential point, i. e., the fact of their combat is recorded in the sources very well.

[14] This ritualized archetypical combat is rooted in a very ancient religious idea that the leader taking part in this combat is the embodiment of all his people and their sacred force — see: Hoffman W. Die Polis bei Homer // Festschrift für Bruno Snell. Hrsgb. H. Erbse. München, 1956. S. 158.

[15] Bosworth A. B. Conquest and Empire… P. 45 f.

[16] Parke H. W. The Massacre of the Branchidae // Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS), 1985. Vol. 105. P. 59, 62, 65.

[17] See the overview of the discussion concerning this episode in: Bettenworth A. Jetzt büßten die Nachfahrer die Schuld ihrer Ahnen. Das Problem der Branchidenepisode bei Curtius Rufus // Der römische Alexanderhistorker Curtius Rufus. Hrsg. H. Wulfram. Wien, 2016, S. 189–208.

[18] ne of the considerations supporting this assumption is that actions like this were supposedly not characteristic of Alexander: Demandt A. Alexander der Große. Leben und Legende. München. 2009. S. 204.

[19] Tarn, for example, rejected the historicity of this story maintaining that in Xerxes’ time there was no temple of the Branchidae in Didyma yet: Tarn W. W.: 1) The Massacre of the Branchidae // Classical Revue. 1922. Vol. 36. P. 63–66; 2) Alexander the Great. Vol. II. Sources and Studies. Cambridge, 1948. Р. 272–275. There was also a view that the whole story was a literary fiction: Fontenrose J. Didyma: Apollo’s Oracle. Cult and Companions. Berkeley, 1988. P. 12.

[20] Parke H. W. The Massacre… P. 68; Bosworth A. B. Conquest and Empire… P. 109.

[21] Kubica O. The Massacre of the Branchidae: a Reassessment: The Post Mortem Case in Defence of the Branchidae // Alexander the Great and the East: History, Art, Tradition. Eds K. Nawotka, A. Woiciehowska. Wiesbaden, 2016. P. 143–150.

[22] Taeger F. Charisma… P. 197f; Badian E. The Deification of Alexander the Great // Ancient Macedonian Studies in Honor of Charles F. Edson. Ed. by H. J. Dell. Thessaloniki, 1981. P. 46–47. 22 Nawotka K. Alexander the Great… P. 273.

[23] Ibid. 65.

[24] Ibid. 67f.

[25] Kubica O. The Massacrae of the Branchidae… P. 148.

[26] Hammond N. G. L. The Branchidae at Didyma and in Sogdiana // Classical Quarterly. 1998. Vol. 48, no. 2. P. 344.

[27] Bettensworth A. Jetzt büßten die Nachfahrer… S. 203f.

[28] See more in: Bettensworth A. Jetzt büßten die Nachfahrer… S. 205f.

[29] Nilsson M. P. Geschichte der griechischen Religion. Bd. 2. München. 1955. S. 14.

[30] Here is only a part of the cases: Diod. XVII. 17. 3; XVII. 72. 1; XVII. 89. 3; XVII. 100. 1; Curt. III. 12. 27; IV. 13. 15; VII. 7. 8–29; VIII. 2. 6; IX. 1. 1; IX. 4. 14; Plut. Alex. 15; 19; 43; Arr. Anab. I. 11. 6–7; II. 5. 8; II. 24, 6; III. 5. 2; IV. 8. 2; V. 3. 6; V. 20. 1; VI. 19. 4; VII. 14. 1; VII. 24. 4; VII. 25. 3; Just. XII. 10. 4.

[31] Instinsky H. U. Alexander der Grosse am Hellespont. Würzburg, 1949. S. 28ff; Heckel W. Alexander, Achilles and Heracles… P. 21f.

[32] Some basic psychology should be considered: a cynical and pragmatic politician would never do most of what Alexander did: would not risk leading an army into a battle, enter Gordium, look for oracles in a desert, attack inaccessible cliffs, build “unnecessary” altars, fight the desert in Gedrosia, etc. Altogether, such a politician would never start an adventurous and risky campaign like that…

[33] Alexander’s disposition towards mysticism and the irrational cannot go unnoticed, and it is no surprise this trait of his personality has been noted and stressed by researchers — see for instance: Tarn W. W. Alexander der Grosse. Bd. 1, Darmstadt, 1968. S. 128; Wilcken U. Alexander der Grosse. Leipzig, 1931. S. 49, 61; Bengtson H. Philipp und Alexander der Grosse. Die Begründer der hellenistischen Welt.München, 1985. S. 157, 210; Hammond N. G. L. The Branchidae at Didyma and in Sogdiana… P. 7, 64, 199; Brunt P. A. The Aims of Alexander // Alexander the Great. Ed. by I. Wortington. London, 2003. P. 46f; Fredricksmeyer E. Alexander’s Religion and Divinity // Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great. Ed. by J. Roisman. Leiden, 2003. P. 267.

[34] It must be understood that using certain mystical elements, like dreams, to promote and raise the spirit of the troops does not give any ground to deny Alexander’s beliefs in mysticism. At the same time, we will never know which dreams were real and which — fake.

[35] Atkinson E. A. A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus Historiae Alexandri Magni. B. 5 to 7,2. Amsterdam, 1994. P. 198.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Baynham E. Alexander and the Amazons // CQ. New Series 51. 2001. Vol. 1, P. 115–126; Atkinson E. A. A Commentary on Q. Curtius Rufus… P. 198.

[38] See: Huttner U. Die politische Rolle des Heraklesgestalt im griechischen Herrschertum. Stutgart, 1997. S. 92–112, 116ff; Fredricksmeyer E. Alexander’s Religion and Divinity // Brill’s Companion to Alexander the Great. Ed. J. Roisman. Leiden, 2003. P. 262; Heckel W. Alexander, Achilles and Heracles…P. 25–30.

[39] I do not understand the word legitimation in its narrow meaning here as a way of making some political action legitimate, i. e., corresponding to the letter of the law; I use it in a broad meaning as the way of securing the acknowledgement of this action in society, regardless of the letter of the law. The most vivid examples of this informal legitimation in the history of Ancient Greece are Peisistratus’ second rise to power [Hdt. I. 60; Arist. Ath. Pol. 14. 3–4] and Herodotus’ story about the Lydians accepting Gyges’ seizing the throne after the Delphic oracle approved of it [Hdt. I. 12]. It does not matter now how everything really happened; what is important is the fact that this type of legitimation was acceptable for the ancient Greeks. Therefore, it is not surprising that the tyrants of the Archaic Age usually resorted to this informal legitimation and did not legalize their power institutionally, i.e., they did not hold any formal office — see: Welwei K.-W. Athen. Von neolitischen Siedlungsplatz zur archaischen Grosspolis. Darmstadt. 1992. S. 249 f; Berwe H. Wesenzüge der Griechischen Tyrannis // Die ältere griechische Tyrannis bis zu den Perserkriegen. Hrsg. K. Kinzl. Darmstadt. 1979. S. 177; Sancisi-Weerdenburg H. The Tyranny of Peisistratos // Peisistratos and the Tyranny: A Reappraisal of the Evidence. Ed. by H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg. Amsterdam, 2000. P. 5–6, 14.

[40] A parallel can be found with ancient Rome again, where both written laws (leges) and unwritten norms (mores maiorum) were regarded as equal sources of law. Similarly, in Islamic law, the official norms of shariah take into account adat, i. e., local unwritten customary norms practiced by the Islamic people.

[41] On the concept of two types of laws in the creative work of Sophocles see: Ehrenberg V. Sophocles and Pericles. Oxford, 1954. P. 22f, 35f, 162.

[42] See: Waterfield R. Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths. London, 2009. P. 168; Colaiaco J. A.

Socrates against Athens: Philosophy on Trial. New York, 2001. P. 6, 8.

[43] See: Surikov I. E. Antichnaya Gretsiya. Mental’nost’, religiya, kul’tura. Moscow, 2015. P. 213–219.

[44] On the formal grounds of legitimization of Alexander see: Badian E. Alexander the Great between Two Thrones and Heaven: Variations on an Old Theme // Subject and Ruler: The Cult of the Ruling Power in Classical Antiquity. Papers Presented at a Conference Held in the University of Alberta on April 13–15, 1994, to Celebrate the 65th Anniversary of D. Fishwick / ed. by A. Small. Ann Arbor, 1996. P. 11–26. — See also: Dreyer B. Heroes, Cults, and Divinity // Alexander the Great. A New History / eds W. Heckel, L. A. Tritle. Oxford, 2009. P. 218–234.

[45] See: Brunt P. A. The Aims of Alexander… P. 45f; Flower M. Alexander the Great and Panhellenism // Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Eds A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, 2000. P. 96–135; Habicht C. Gottmenschentum und Griechische Städte. 2. Aufl. München, 1970. S. 17–36; Kholod M. M. The Cults of Alexander the Great in the Greek Cities of Asia Minor // Klio. Beiträge zur Alten Geschichte. 2016. Bd. 98.2. P. 495–525.

[46] Moreover, if the ideas of revenge and liberation had been exhausted after capturing Persepolis, the idea of heroic war became the central one starting from that moment.

[47] See: Mehl A. DORIKTETOS CHORA. Kritische Bemerkungen zum “Speererwerb” in Politik und Volkerrecht der hellenistischen Epoche // Ancient Society. 1980/81. Vol. 11/12. P. 173–212; Chaniotis A. War in the Hellenistic World: A Social and Cultural History. Oxford, 2005. P. 181f. — it should be emphasized that it really was the oldest right; therefore, it is totally wrong to suggest that Alexander did not have any right to lay claim to the Persian throne (Wortington I. By the Spear. Philip II, Alexander the Great and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire. Oxford, 2004. P. 199); it would mean imposing modern ideas about legitimacy on Alexander. As history shows, the right of war was actually the strongest right in the ancient world. Besides, Alexander did not literally intend to become the king of Persia; he created his own kingdom incorporating Persia and Persian elements into it: Fredricksmeyer E. Alexander the Great and the Kingship of Asia // Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Eds A. B. Bosworth, E. J. Baynham. Oxford, 2000. P. 136–166.

[48] See: Garlan Y. War in Ancient World: A Social History. London, 1975. P. 75 f.; Austin M. Alexander and the Macedonian Invasion of Asia: Aspects of the Historiography of War and Empire in Antiquity // Alexander the Great. Ed. by I. Wortington. 1995. P. 118–135; Billows R. King and Colonists (Aspects of Macedonian Imperialism). London. 1995. P. 25f.; Brunt P. A. The Aims of Alexander… P. 46f. — The Roman custom of declaring war by hurling a spear vividly confirms the age and universality of the “right of a spear”. Another Roman parallel is the archaic legal practice vindicatio, which involved the uttering of a sacred formula confirming the right to own certain property holding a stick (vindicta) in an outstretched hand, which symbolized the readiness to fight for this property with arms, i. e., the stick symbolized a spear.